Psalms and Daffodils

(How to sing Anglican Chant)

by Peter Balkwill

This article was written for members of the Junior Choir who are studying for their RSCM medals, as singing Anglican chant is part of that syllabus. However it may well be of interest among the many others who would like to enjoy singing psalms, but find the way to sing them a bit of a mystery. Here, Pete unravels the secrets for us and provides many interesting facts along the way.

The psalms are a collection of songs from a book of the Bible sometimes referred to as the Songs of David, although we know that they were written by a number of different people. They are a group of Hebrew writings from before the time of Christ which speak about our relationship to God.

They explore every aspect of human emotion and spirituality from joy to despair, hope to fulfilment. Some are majestic and some are humble. In the past they used to be sung just as a melody with a stringed instrument accompanying but over the years Anglican Psalm Chant has developed into one of the most glorious and inspiring forms of music in the Church repertoire!

If you are reading this now, then you will soon be able to join us in this wonderful form of song singing! But why are the psalms so different from other sorts of songs and anthems? And why do we need a different way of writing them down to sing them?

Here is the beginning of a famous poem by Wordsworth you might know:

I wandered lonely as a cloud (8)

That floats on high o’er vales and hills, (8)

When all at once I saw a crowd, (8)

A host of golden daffodils; (8)

Beside the lake, beneath the trees, (8)

Flutt‘ring and dancing in the breeze. (8)

I can just imagine walking through the Lake District on a spring morning and seeing this lovely sight! As you can see it has a rhythm that goes:

Dah dum di dah, da dum di dah,

Dah dum di dah, da dum di dah.

The numbers on the right of each line of the poem show the number of syllables. This called the metre of the poem and as you can see for this rhythm there are 8 syllables or beats in each line.

Hymns are just like this too:

Once in royal David’s city (8)

stood a lowly cattle shed, (7)

where a mother laid her baby (8)

in a manger for his bed: (7)

Mary was that mother mild, (7)

Jesus Christ her little child (7)

This time we have 8 syllables in the first line then 7 in the next and so on until the last two lines which both have 7 syllables. (You can see this metre marked in the hymn book at the top of the hymn as “87 87 77”). So with a regular metre we know exactly when to change note with the words!

Psalms however are not like this because they are written in a special form of prose (see later). Here are the first four verses of psalm 8:

- O Lord our Governor, how excellent is thy Name in all the world: (16)

Thou that hast set thy glory above the heavens! (11) - Out of the mouths of very babes and sucklings hast thou ordained strength because of thine enemies: (23)

That thou mightest still the enemy and the avenger. (14) - For I will consider thy heavens, even the works of thy fingers: (17)

The moon and the stars which thou hast ordained. (10) - What is man that thou art mindful of him: (10)

And the son of man that thou visitest him? (11)

Again, the numbers on the right show how many syllables are in each line – as you can see it’s all over the place! – it wouldn’t fit to a regular tune like you get in a hymn because psalms don’t have a regular pattern of syllables.

Psalms are non-metrical!

We can think about Psalms in two parts – the rhythm and the notes.

To make sense of the poetry of the words when we sing psalms, we need to use the natural rhythm of the words as they are spoken – not to musical notation. We don’t say ‘The cat sat on the mat’ with exactly equal lengths for each syllable:

The : cat : sat : on : the : mat.

But rather…

The cat sat on the mat.

So it is with psalms – the notes are freely chanted according to the rhythm of natural speech, rather than to the musical value of the notes such as a minim or semibreve.

However, we still want to sing to a tune, so we need a system to tell us when to change notes – we call this pointing. Pointing is just a mark in the text which points out to us when to change note in the music, however many syllables we have sung so far.

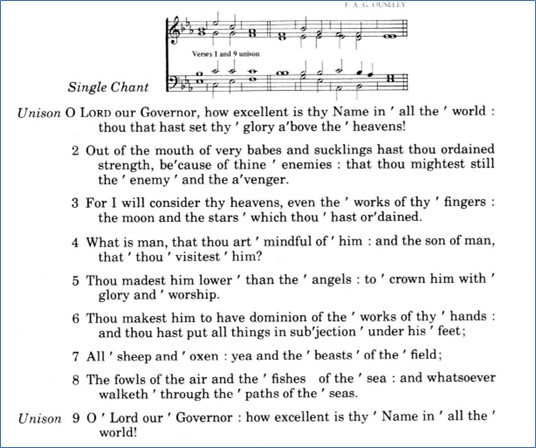

Here is Psalm 8 again, shown now with the pointing so that we can see how many syllables go with each note.

The first thing to take notice of is the tune – it’s the top line of the music which is sung by the congregation, sopranos and trebles. (In this case, verses 1 and 9 are marked as unison so in fact all the lower parts sing this tune in those verses too.) Always listen to the organ playover to hear the tune, because when we start singing we’ll want to focus on fitting the words to the tune.

Starting at verse 1, we can see that the first note lasts throughout ‘O Lord our governor, how excellent is thy name in’. Then there is a small point mark, telling us to move to the next bar, which has the two notes for ‘all the’; and then there is another point mark for the last bar of the line (which is just one note) for ‘world:’

The second line is sung to the second half of the chant, starting with ‘thou that hast set thy’ on the first note. Then there is a point mark, so we go to the next bar which has two notes for ‘glory a-’. Then there’s another point mark, so we move to the next bar which has two notes (of the same pitch) for ‘-bove the’, and another point mark to move to the last bar of the line for the last note on ‘heavens!’

We continue in this way through the whole psalm.

Extra Information

You really don’t need to worry too much about extra information at this stage, but it may be useful and interesting to note.

The most commonly used chants are double chants. These are twice the length of a single chant like the one above. So with a double chant the music covers two verses and is repeated for every pair of verses.

This reflects the structure of the Hebrew poetry of many of the psalms: Each verse is in two halves – the second half answers the idea in the first half. The verses are also in pairs – the second verse answers the first. This kind of symmetry is called parallelism and is the primary poetic device used in the Hebrew verse of the psalms – we get a sense of this even when we see them in English translation.

Each verse is sung to seven bars of music (the whole of the chant in the example above) so we get a sort of rhythm which goes: 1 – 2,3,4 (first line); 5 – 6,7,8,9,10 (second line). Again, this reflects the structure of the Hebrew poetry of the psalms.

As we have seen where there is just one note in a bar, all the words for the corresponding part of the text are sung to that one note. Where there are two notes (two minims) to a bar…

- usually, all the words except the last syllable are sung to the first minim, and the final syllable is sung to the second minim. However…

- sometimes we need to sing more than just the last syllable to the second minim: here a dot (·) (between words) or a hyphen (within a word) is used in the text to indicate where the note change should occur.

That’s it for now, but of course, we’ve only just begun to scratch the surface of how to sing psalms well. To bring out the meaning and emotions expressed by those early poets, we need to think about: how loudly we sing (the dynamics), where we pause, what tempo is used, and, if the psalm is accompanied, how the organist provides colour to the words we sing. All these aspects add a richness to psalm singing that can be immensely rewarding, and a pleasure to listen to.